In San Jose politics, history has a way of repeating itself.

Eight years ago when Mayor Sam Liccardo sought the city’s top political job, the biggest issue on the campaign trail was police staffing levels. That comes as no surprise—Liccardo as a councilmember strongly backed Measure B, a 2012 initiative championed by his predecessor Chuck Reed that slashed police officer pensions. It led to costly lawsuits and an exodus of cops. Liccardo, who once vowed to defend the measure, found himself negotiating a settlement in his first term as mayor to keep the city’s police union happy and settle never-ending litigation.

Now, Liccardo’s newly-endorsed pick for mayor—freshman Councilmember Matt Mahan—finds himself in a similar fight. Once again, the police force’s staffing levels and public safety is at the center of another contentious mayoral race in America’s 10th largest city.

It all began a week ago when the San Jose Police Officers’ Association released a survey that found 200 officers plan to resign soon. Mayoral candidate and Santa Clara County Supervisor Cindy Chavez, who is endorsed by the police union, doubled down by inviting District Attorney Jeff Rosen and the police union leader to her new campaign headquarters last weekend, where she promised to hire dozens of officers as her first action as mayor.

Her campaign then sent texts to voters linking the union survey and calling out Liccardo and Mahan for a “lack of transparency” about the “dangerously low staffing levels” at the police department.

When asked to explain how Mahan is lacking transparency, Chavez’s campaign pinpointed his criticism of policies designed to depopulate jails which Mahan blames for straining the police department. Liccardo has also opposed those policies—some of which allow low-level offenders to be released while awaiting court dates and allowing officers to issue citations for nonviolent crimes instead of arrests.

“Instead of making the community safer by staffing the department up to a reasonable level, Mahan and Liccardo continue to point fingers at the county for the rise in crime, which the San Jose Police Officers’ Association itself has been clear is a city issue since the SJPD need the budget from the city to add more officers,” said Grace Papish, Chavez’s campaign spokesperson.

But Mahan says his opponent is misleading voters.

“Supervisor Chavez has adopted (the union’s) talking points and is also now negotiating for them, one of her most significant financial supporters,” Mahan told San José Spotlight. “Shame on her. Her job is to do what’s best for the public, not her political supporters.”

At the heart of the showdown is a tense, closed-door contract negotiation at San Jose City Hall. The police union is asking city administrators for a 14% raise over the next two years.

To fact-check claims made by both campaigns, here’s a closer look at each talking point:

Officer staffing levels

Here, there appears to be two sets of data—and perhaps it comes down to semantics. How do you define “resignations” and who gets counted as a “separation” when they leave SJPD?

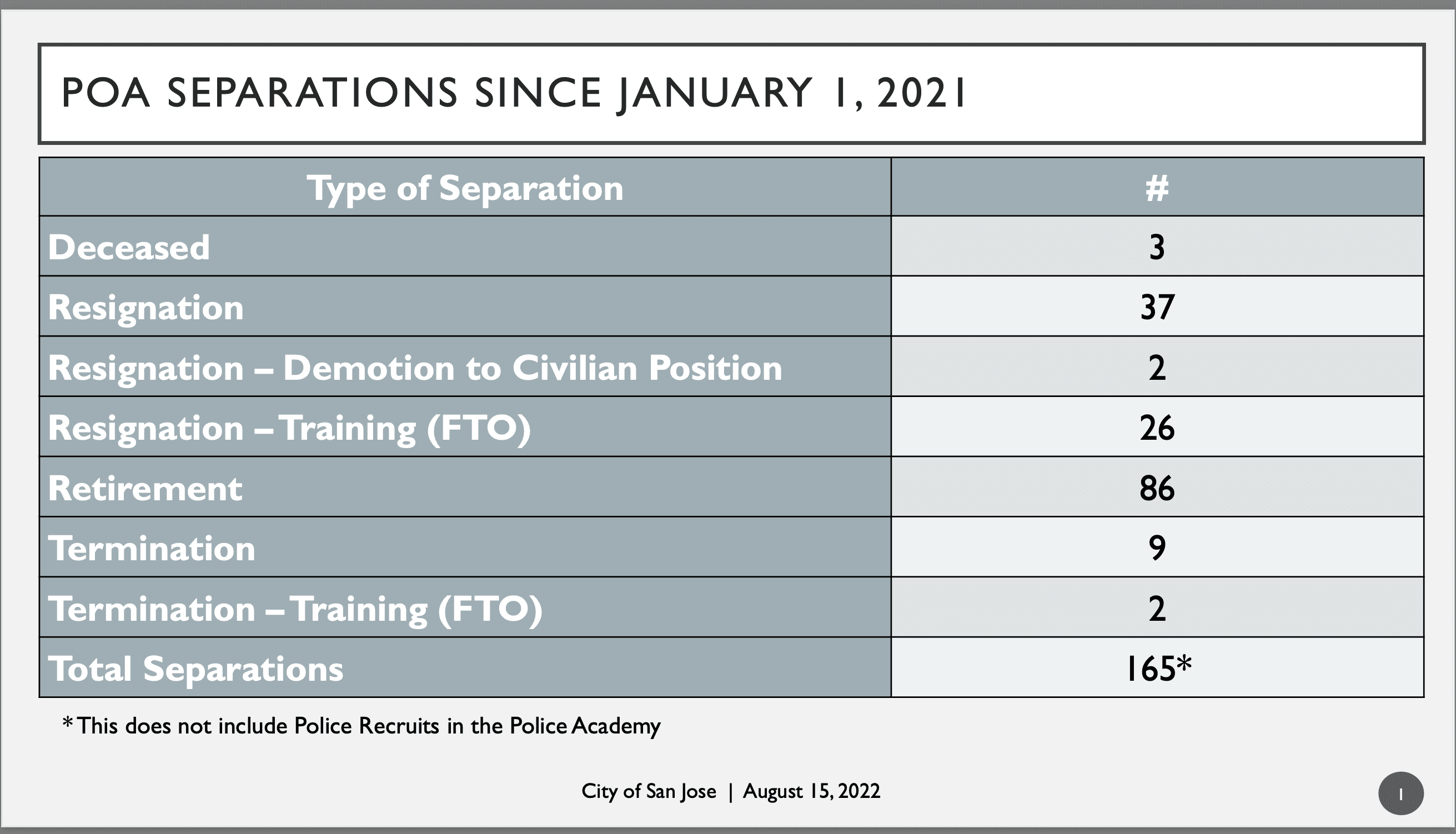

The police union—and by extension, Chavez—have cited a redacted city roster that shows 85 officers have separated from the San Jose Police Department so far this year. The document shows 124 separations last year, bringing the total since January 2021 to 209 officers. The reasons for the “separations” are everything from transfers to dropping out of training, being fired or dying.

Liccardo—and by extension, Mahan—cite a chart, which appears to have been created just last week in response to the union’s claims, that shows 165 officers were separated since January 2021. Those numbers are supported by city administrators. In an op-ed this week, Liccardo added that only 37 officers with at least 20 weeks of experience left the department for other work, linking to the same document. Notably, the figures don’t include police recruits in the academy.

But a nonredacted roster of officer separations from January 2021 to this July confirmed the union’s number. The document, obtained by San José Spotlight, was prepared in July by a city analyst. The analysis shows 209 sworn officers—including 47 recruits in the academy—have left the department since January 2021.

City spokesperson Carolina Camarena said the discrepancy is because the city left out police cadets in the academy from its figures, which were cited by Liccardo and Mahan.

Liccardo’s spokesperson Rachel Davis referred questions to Camarena.

“We have tried to coordinate with the POA regarding the data discrepancy, but they have not been responsive,”Camarena told San José Spotlight.

Today, the department has 1,157 full-time sworn officers—201 fewer positions than the 1,358 in 2000—despite the city’s population growth. The staffing levels have forced mandatory overtime for officers and led to longer response times for calls ranging from stabbings to property damage and missing persons.

Vacancy rates

The San Jose Police Department’s current vacancy rate is 2.56%, according to the city, and it is considered among the lowest in the region. But police union spokesperson Tom Saggau said the rate is irrelevant because the total number of sworn officers is much lower than 20 years ago and response times for crime has shot up.

“Sounding more like a carnival barker than a mayor, Liccardo keeps repeating that the vacancy rate is low in his latest snake oil salesman scam,” Saggau told San José Spotlight. “The vacancy rate is lower because the number of authorized officers is lower.”

Union leaders also say the city is manipulating the numbers by counting every person in the department—including recruits in the police academy—while it left this population out of its separation report. An estimated 30% to 40% of those cadets drop out of training and don’t join the police force, the union estimates. They argue those individuals should not be counted as filled positions.

Chavez’s campaign pointed to data from the FBI that shows San Jose has 1.1 officers for every 1,000 residents—the same rate as the city of Bakersfield which has about half the residents.

Another disagreement: Liccardo said the union wants the city to consider the positions of injured officers as “vacant” since they’re not on the job. That logic doesn’t pencil out, the mayor argued, because they’re still collecting a salary.

Crime is going up

Mahan and Liccardo say violent crime has spiked in Silicon Valley. They blame Chavez and other county leaders for supporting policies to reduce the jail population.

Recent data from the San Jose Police Department shows the number of rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults have increased from 2020 to 2021, though murders are down. Overall crime in the city dropped 4% over the one-year span, mostly sparked by a decline in property crimes such as vehicle thefts and burglaries.

Still, justice advocates say there is no correlation between those policies and an increase in violent crime.

Solutions

The two candidates vying to be San Jose’s next mayor don’t agree on much, but each have mapped out a plan to bolster the city’s police force.

Chavez promises to secure additional funding in the city budget to hire a significant number of new officers. The San Jose City Council last month approved adding 16 new officers to patrol neighborhoods and four to the mobile crisis assessment team.

“My first action as mayor will be to fund 45 additional sworn officer positions annually, tripling the current approach by City Hall,” Chavez said.

Mahan wants to support police officers by ending county measures to depopulate jails—which he called “misguided catch-and-release” policies—while boosting city revenue to support hiring more cops.

“Money doesn’t grow on trees,” Mahan said. “To increase the rate at which we’re adding officers each year we have to attract jobs and economic activity to grow our tax base.”